英国斯坦费尔德先生回忆亲历中国抗战纪实

——英国斯坦费尔德先生亲历中国抗战和在京见证日军受降典礼回忆

英国约翰·斯坦费尔德先生是一位94岁的老人,现安康地居住在英国西南部。70年前,他受英国派遣来中国参加抗日战争,并见证了1945年在北京太和殿举行的中国华北战区(第11战区)日军向盟军投降仪式,且作为英国代表在日军受降书上签字。欣闻9月3日中国将举行纪念大会和盛大阅兵,庆祝中国人民抗日战争暨世界反法西斯战争胜利70周年,特撰写回忆文章,希望让更多的人了解当时的情况。汪仲远夫妇为斯坦费尔德先生与我国相关部门联系发挥了桥梁作用,在此一并感谢。下面是斯坦费尔德先生撰写的回忆文章。

John Stanfield (图片由汪仲远夫妇提供)

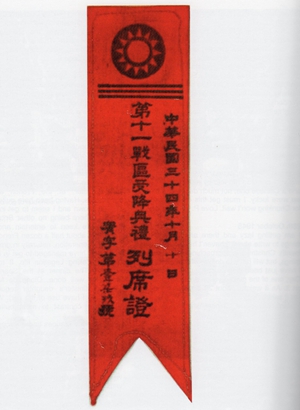

John Stanfield的列席证 (图片由汪仲远夫妇提供)

序言

对于英国人来说,第二次世界大战是从1939年8月德军入侵波兰开始的。对于中国而言,战争要早好多年,是从臭名昭著的“二十一条”和日军随后对满洲的蚕食入侵开始的。最初并未宣布战争,直至1937年冲突全面爆发,该年底日军占领了中国沿海许多城市。这种公然的侵略令全世界骇然,但一直到1941年日军袭击珍珠港,入侵东南亚,美英才被卷入对日战争并开始与中国结成联盟,反对共同的敌人。

由于日军控制了沿海,要进入中国十分困难,最终,从印度起飞,飞越喜马拉雅山脉进入中国的西南部昆明,成了出入中国的唯一途径,所以仅有少量的军事装备和人员送入中国,这些人员中包括了英国特别行动局(SOE)136部队。特别行动局是英国首相温斯顿.丘吉尔为反击被占领国的敌军而成立的组织,而136部队是其在远东执行任务的主要部队。1943年我就是被派往该部队的一位年轻的英国军官。

从英国到中国

我的父母是在中国的传教士。1921年,我出生在汉口(武汉),我和我的姐妹从小在中国孩子中间长大,当然也学汉语。在三十年代,我被送回英国学习。1939年8月,我的父母刚从中国返英,长沙大火时,他们的住处同样也被烧毁,而我刚入读利物浦大学。当战争开始时,我被征召入伍,进入皇家“通讯”兵团,接受了包括无线电通信理论和实务、野外生存、使用武器、驾驶车辆等训练。

1941年我被送到“军官学校”学习,1942年我成了炮兵部队“通讯部门”的一名中尉军官,然后1943年初我被派往印度,在旧德里的陆军总部掌管通讯办公室。

我不喜欢旧德里,又脏又热,工作也无聊。幸运的是我在人事调配部有位朋友,她知道我会讲汉语,把我的名字提供给特别行动局(SOE),更为幸运是他们碰巧正在寻找一位能去中国工作的通讯军官,因而很快我以上尉的军衔被派往M.E.9, 一所在印度北部的间谍学校学习,同许多国家的无线电报员和谍报员一起接受秘密工作的训练,几个星期后,我被授予BB669代号,准备接手136部队中国通讯部副指挥的工作。

在M.E.9我学习了密码、编码以及如何使用提供给我方谍报人员在敌后使用的各种型号的无线电设备,先是被伪装成像个普通手提箱的A3设备,接着是功率强大的B2设备,它能够从中国与印度联系。我的训练很快就结束了,1944年春天我被派往中国,坐飞机飞越喜马拉雅山,空降至昆明。

1944年在中国

昆明是个令人愉快的城市。至今我的眼前还能回想出这座城市的景象,群山围绕着美丽的滇池。我们136部的办公室就设在西山脚下沿湖13英里处西山一栋老房子里,约有15位英国和中国的信号员住在那里。我们为印度与重庆之间的谍报机构送发情报信息。工作是轻松的,但干了不久,我就受命前往我们在桂林的前沿基地。

桂林距离昆明约500英里。一辆破旧的卡车上在崎岖不平的路上行驶了四天,终于到达目的地。在桂林,我是136部队办公室的负责人,办公室包括3名英国人和20名中国人,主要任务是为我们的情报机构服务,支援中国军队以及英国军事援助团(BAAG)。这个组织主要由日寇入侵后从香港逃出来的英国和中国士兵组成,他们收集日军在华南行动的情报,由我们转送至重庆和旧德里。

遗憾的是日军没有让我们太平。9月,他们从长沙南边发动了一场大扫荡(代为‘一号作战’计划)以破坏美国建设空军基地的计划,并从满洲里至缅甸前线开辟了一连贯的由日军控制的陆地走廊。桂林也在其中,‘一号作战’计划对于处在这条通道范围内的人们来说简直是场噩梦,中国在这个地区没有足够的兵力阻止日军,因此中国军队和我们不得不撤退。

中国人从桂林(25万人口的城市)撤离了。我记得,撤离的前一天晚上,看到燃烧的城市火光冲天,爆炸的火光照亮了天空,公路和铁路挤满了难民。情势恐怖,但没有人愿意和日寇在一起。

我们很幸运能乘坐我们又破又旧的卡车撤离,但由于没有汽油,我们只能用能量很小的低辛烷甲醇来代替。

从桂林撤退到昆明的路线要经过宜山、独山和贵阳。路途艰辛而漫长,我们饱受疾病、设备故障和供应短缺的困扰,但依然保持了电台的工作,用蒸汽发电机给电池充电。

最终,我们回到了昆明。我接管了136部队办公室,一直干到1945年我被再次任命为在西安的华北地区通信部负责人,与中国军统局(DMI)协同工作。

先坐飞机到昆明,再驱车4天,经成都抵达西安,随行的还有中国军事情报局的郝侃曾少将和2名英国通信兵,这2名英国通信兵将去培训郝少将的部下使用英国无线电台。那时的西安有城墙围绕,一派古城风貌。第一个月我没有什么事情,但到6月下旬,我接到任务要在黄河边的战略要地、近华阴的村庄附近设立2个室外无线电站,供情报人员发来日本人活动的情报。

我需要调动7个人员以及大批无线电设备。为此我动用了一辆吉普车和一辆25吨的拖车。至今我已经习惯了中国糟糕的路面,从西安到华阴的路程是我一生经历过的最艰难的驱车路程,汽车在尖崖峭壁、积土厚重的路面上前行,大多数路程我不得不用低档开车,没有其它车辆能比吉普车更能适应这样的路程。

我们终于到达华阴一个离我们目的地最近的村庄,非常贫困的地方,被日寇炮火损坏严重。村民们吃苦耐劳、待人友好。附近有一个美国战略情报局的无线电台执行与我们相同的使命。任务完成后我回到西安,见到英国高级军官布里奇上校,他来此与中国军事情报局联络由136部队为骚扰日军的游击部队提供装备、武器和通信设施之事。8月初我依然在西安忙于制定武装游击部队的计划。

战争结束

1945年8月,我在参加一个晚宴时听见街上有叫喊声,我们让一个男孩出去了解发生了什么事情。他回来拿着一张报纸(见照片)大标题“威力巨大的炸弹摧毁了日本两座城市!日本人投降了!”。周围一片惊讶。就在昨天我们还在制定攻击日军的计划,而今天一切结束了。

接下来相当长的一段异常安静的间歇时间,不断有战俘来看我们。重庆的信息来了,命令郝将军、布里奇上校、斯坦费尔德(作者)和他的一些通讯兵立即飞往首都。9月14日,道格拉斯DC3飞机戴着我们飞行了3小时抵达北京颐和园附近的西郊机场。一队穿着长筒靴、佩戴军刀的日本军官迎接我们,用一队豪华的日本军车送我们进城。我们占据了北京饭店三楼,我建起了一个无线电台。我们像游客一样住下来。形势显得很不寻常,日本卫戍部队依然全副武装,协同中国人和美国人(他们陆陆续续抵达)维持秩序直到被替换。

然后,我的上司布里奇上校被调回重庆接管136部队办公室,我留下来负责北京的事务,我和我的几位通讯兵成了华北唯一的英国军事单位。不久之后,重庆传来信息通知我被已被提升为上校,并指示我必须代表英国,参加10月10日国庆日(中华民国-作者按)举行的日军在华北的官方投降仪式。

我不得不打扮一下,因为我依旧穿着破旧的热带束腰衣裤,看上去很寒酸。我找到一位裁缝,采用日本军官用的最上等的料子做了一身漂亮的军服。

10月10日在北京的受降仪式

仪式结束后我马上作了如下记录:

仪式是在紫禁城太和殿前的平台举行的,就是五百年来中国皇帝宣布胜利的地方。如此背景和日子的完美结合使这一事件与中国历史中的历次事件一样引人入胜、令人惊叹。

太和殿位于紫禁城中心,内有皇帝的龙纹宝座,屋檐和木制品漆着或装饰着金龙。立柱和墙是深红色的。今天是双十节(译者注:中华民国国庆),汉白玉栏杆和台阶插满了盟军国旗。阳光灿烂,照得屋顶黄色的琉璃瓦闪闪发光。

汽车载着我们英国小队人马开往紫禁城,行进在北京街道上,通过拥挤在凯旋门下欢呼的人群,凯旋门插满四大国——中英美苏的国旗。汗流浃背的士兵为我们从人山人海、激动的人群中开出一条道让我们的车通过。到达紫禁城的午门,再经过50码长的过道我们来到广场的另一边,在此下车继续步行。我们走过两段台阶来到太和门。经过太和门时,我们看见下面太和殿前巨大的广场上人山人海,至少有十万人,一直到大理石台基和通向殿前平台的台阶,所有地方都挤满了人群。

台基上装饰五彩缤纷的彩旗,可以看到宫殿的红色立柱后、两侧入口的墙上覆盖了中英美苏的国旗。这情景太壮观了,我们通过列队的士兵,走上三段台阶向平台走去时,一片欢呼声响起,我们有一阵感觉自己好像是宇宙的中心。

平台上铺着一块皇帝的龙毯,上置一张放着日军投降文件的桌子。

中国政府很明智地花费许多时间进行筹备工作。各代表团成员都佩戴着官方红绸标识,我们在阳光下闲逛、拍照片。身穿长袍神态庄严的官员们、穿着漂亮的高领制服的中国将领们、美国海军和空军军官们以及我们英国代表——我、大使馆高级官员和两名低级军官,被前来观看受降仪式的各国百姓观光者们簇拥着。

一位中国将军陪同我代表英国军队在受降书上签字。受降文件是四本像折叠的像手风琴般的书,用黄绸带扎住,用可吸毛笔墨汁的吸水纸做成。

这期间,每一次欢呼声响起都揭示一批新的显要人物的到达,负责受降仪式的高级军官随后引领官方的观礼者,外国人在左侧,中国人在右侧,我们背对大宫殿,军乐队站在两侧,前面空地留给日本人。

当一切就绪,当中国华北战区司令官孙连仲将军与他的随从们从宫殿走出,来到阳光下,负责仪式的主持人指示百姓摘下帽子而我们军人敬礼。

一位副官要求把日本代表带上前来。一声呐喊声响起,表明日本军方正走在足有二百码长、被中国观礼群众包围的巨大广场。当他们走上三层台阶时,呐喊声变成了胜利的欢呼声。长达七年(编者注:应为14年)的侵略战争将要以这些军官的耻辱来结束,他们就将在过去五百年来被中国打败的敌人放弃权利的象征的地方,交出他们的军刀。

日本军人在孙将军面前排成一排,立正,敬礼并列队向左候命。孙将军命令日军在华47师司令官在投降文件上签字。日军司令官走近桌子用准备好的毛笔签了字,然后孙将军签字。接着孙将军命令道:“现在交出你们的军刀”。在高级将领的带领下,日本军官一个个走向桌子,解下军刀,放下。再次列队,敬礼,转身向右走。孙将军敬礼,转身离去,回到太和殿。昏暗的立柱深处,立着巨大的龙椅…..观礼群众受邀向联军祝贺。

我们的离开是又一次的凯旋游行。当我们通过宽阔的广场和宫殿时,人群再一次鼓掌和欢呼,感觉仿佛从十五世纪回到了二十世纪。

我感到情感枯竭了。眼前的这一幕现实太具有纪念意义、太生动了:金色的砖瓦、深红色的围墙、汉白玉的栏杆和欢呼的人群,这样的场景一个时代只会发生一次。对中国来说,这个投降仪式是日本战败的最重要的时刻。

这一定是亚洲或许是全世界最壮观、最激动人心的投降仪式,但由于通迅不好,在中国之外几乎没有什么报道。

仪式之后

接下来的两个月渐趋平静,我专注于改造旧的英国大使馆。美国的军事存在继续加强,外交官们陆续返回,社交活动很多。

12月12日,我关闭了136部队办公室,离开北京接受新的任务,成为香港通讯工作的负责人。后于1946年3月乘船返回家乡英格兰,并离开了部队。后来,我进入剑桥大学先后读了经济学、神学,并在卫理公会的教堂开始新的生活。经历了六年的战争,终于结束,在经历了那么久的分离后终于回到了家庭,回到了家,看到这一切我是多么高兴啊!

附:英文原文

EYE WITNESS TO THE JAPANESE SURRENDER IN BEIJING ON 10.10.1945

The following is written by John Stanfield, a fit and healthy 94 year old gentleman, now living in South West England. 70 years ago he witnessed the ceremony in Beijing when the Japanese Army surrendered to the Allies, and he signed the surrender document on behalf of the British Army.

PROLOGUE

For English people, World War II started in August 1939 when the Germans invaded Poland. For China, the war started many years earlier, with Japan’s infamous ’21 Demands’ and their subsequent encroachment into Manchuria. Initially this was an undeclared war, and then in 1937 it became a full scale conflict. By the end of the year Japanese forces occupied much of coastal China. The world was horrified by this blatant aggression, but it was not until December 1941 when Japan attacked Pearl harbour and invaded South East Asia that America and Britain were drawn into the war against Japan, and became allied with China against this common enemy.

As Japan gained control of the coast, access to China became very difficult, and eventually the only way in and out of the country was by air from India, over the Himalayan Mountains to Kunming in the South West. Only small quantities of supplies and personnel could be sent into China.... and these personnel included men of Force 136 of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). SOE was a subversive force established by British premier Winston Churchill to undermine and attack enemy forces in occupied countries, and Force 136 was its main Far East unit. This was the organisation to which I, as a young British officer, was posted in 1943.

FROM ENGLAND TO CHINA

My parents were missionaries in China, and I was born in Hankou (Wuhan) in 1921.My sisters and I grew up surrounded by Chinese children, and of course we learnt Chinese. In the 1930s I was sent back to school in England. In August 1939 my parents had recently returned from China, having lost their home in Changsha when the Japanese burnt the city. For my part I had just entered Liverpool University. When war was declared, I was drafted into the Army’s ‘Signals’ organisation. Training involved the theory and practice of radio, field-craft, learning how to fire weapons and how to drive vehicles. In 1941 I was sent to ‘officer school’ and in 1942 I became a lieutenant in the Signals Section of an Artillery unit. Then at the beginning of 1943 I was sent to India where I was assigned to run the signals office at Army Headquarters in Delhi.

I did not enjoy Delhi. The town was hot and dirty and the work was boring. Luckily I had a friend in the Personnel Postings Office and she, knowing that I could speak Chinese, put my name forward to SOE; and as luck would have it, they happened to be looking for signals officers to serve in China. So very soon afterwards, I found myself posted (with the rank of captain) to M.E.9, a ‘school for spies’ in Northern India, where agents and wireless operators of many nationalities were trained for secret work. In the weeks that followed I was given the code name BB669 and made ready to take up the job of ‘second in command’ of Force 136 China Signals.

At M.E.9 I learnt about ciphers and codes and how to use the various types of radio sets supplied to our agents behind enemy lines. First the A3 set that was disguised to look like an ordinary suitcase; then the more powerful B2 set, which could communicate from China to India. For me the training was soon over and in the spring of 1944 I was despatched to China by air over the Himalayas to Kunming.

CHINA 1944

Kunming was lovely when I arrived, and I can still picture the city and its beautiful lake surrounded by mountains. Our Force 136 office was 13 miles along the lake at Shi Shan under the Western Hills. There were about 15 British and Chinese signalmen living in an old house there. We worked to India and up to Chunking, relaying messages from our agents. This was a comfortable post, but it didn’t last long as I was soon ordered to move to our forward base in Kweilin.

Kweilin was nearly 500 miles away from Kunming. The journey took four days over bad roads in a worn-out truck. But somehow the truck completed the journey. At Kweilin I was in charge of the Force 136 office, which comprised 3 Britons and 20 Chinese operators. Our main tasks were to service our agents, support local Chinese forces and units of the British Army Aid Group (BAAG). This organisation was formed mainly of British and Chinese soldiers who had escaped from Hong Kong after the Japanese invasion. These men were now collecting intelligence on Japanese movements in South China, which they relayed to us for onward transmission to Chungking and Delhi.

Sadly the Japanese did not leave us in peace. In September they launched a major drive (The ‘Ichi-go Offensive’) south from Changsha to disrupt the American air base construction programme and to create a continuous Japanese controlled land corridor from Manchuria, to their front lines in Burma. Kweilin was in the way, and the Ichi-go Offensive was a nightmare for those in its path. There were insufficient Chinese forces in this part of the country to resist the Japanese, so the Chinese – and we - had to retreat.

The Chinese evacuated Kweilin (a city of a quarter of a million people) and I remember the evening before we left, watching the city burn with flames and explosions lighting up the night sky. The roads and the railway were packed with refugees. Conditions were grim, but nobody wanted to be around when the Japanese arrived.

For our part, we were fortunate in being able to get away in our decrepit old trucks. Petrol was unobtainable and we ran our vehicles on low octane wood alcohol which gave very little power.

Our line of retreat led from Kweilin back to Kunming via Yishan, Dushan and Kweiyang. The journey was long and hard. We were beset by illness, breakdowns and shortages but managed to keep our radios going, using a steam-driven generator to charge our batteries.

Back at Kunming at last, I took over the Force 136 office. A job I held until I was reassigned in May 1945 as Officer in Charge of Signals in North China, based in Sian and working with the Chinese Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI).

So a flight to Chunking, and a four day truck ride to Sian via Chengdu in company with Major-General Ho Kan Tzen of the DMI and two English signallers who were to train General Ho’s staff in the use of our English radio sets. At the time of our arrival, Sian was still surrounded by high walls and the city had an antique appearance. My first month was uneventful, but in late June I had the task of establishing two ‘out-station’ wireless posts at strategic points on the Huanghe River near the village of Wa Yin, to which agents could bring information about Japanese movements.

I needed to move seven men and a large quantity of radio equipment. To do this I had a jeep and a quarter ton trailer. By now I was used to China’s poor roads, but the track from the Sian rail head to Wa Yin was the toughest drive of my life. Precipitous cuttings and gorges and deep, deep dust. Most of the way I had to use low ratio gear. No vehicle other than a jeep could have done it.

We finally arrived at Wa Yin, the village nearest our destination. A very poor place, much damaged by Japanese shell fire, but with tough welcoming inhabitants. An American OSS radio post was nearby with a similar mission to ours. having completed the task, I returned to Sian to meet Colonel Bridge, a senior British officer who had arrived to liaise with DMI concerning plans to equip a guerrilla force to harry the Japanese. Force 136 would supply equipment, weapons and communications. Early August found me still in Sian, busily drawing up plans for this guerrilla army.

THE END OF THE WAR

On August 8 1945 I was at a dinner party when we heard shouting in the street. A boy was sent out to find out what was happening, and he returned with a news sheet (see picture) headlined ‘Extraordinary bombs of enormous power have destroyed two cities in Japan and the Japanese have surrendered’. Astonishment all around. Only yesterday we were planning attacks on the Japanese, and now everything stopped.

There followed a strangely quiet interlude. A trickle of prisoners of war came to see us. Then a signal arrived from Chunking. Major-General Ho, Colonel Bridge, Stanfield and some of his signallers were instructed to fly at once to the capital. On Sept 14 a DC3 Dakota aircraft was sent for us, and we flew the three hour journey to Beijing’s West Airfield near the Summer Palace. We were met by a party of Japanese officers wearing swords and high boots. A fleet of luxurious Japanese Army staff cars transported us into town and we took over the 3rd floor of the Beijing Hotel, where I established a radio station. We settled in and behaved like tourists for a few days. The situation was extraordinary. The Japanese garrison was still armed and cooperating with the Chinese and Americans (who were starting to arrive), to keep order until they could be replaced.

Then my boss Colonel Bridge was transferred back to Chunking to take over the Force 136 office, and I was left in charge in Beijing with my small staff of signallers. We were the only British military unit in North China. Soon afterwards, a signal arrived from Chungking telling me that I had been promoted to Major, and I was alerted that I must represent Great Britain at the official surrender ceremony of the Japanese Army in North China on National Day on October 10.

I had to do something about my appearance as I looked very scruffy in my well worn tropical tunic and trousers. So I found a tailor who made me a smart new service uniform ... using the best quality Japanese officers drill material.

THE SURRENDER CEREMONY IN BEIJING ON 10 OCTOBER 1945.

I wrote the following account immediately afterwards.

“The ceremony took place on the Dragon Pavement in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the Grand Coronation Palace in the Forbidden City.... the exact place where for the last five hundred years the Emperors of China have come to announce victories. The setting and the day combined to make this event as colourful and awe-inspiring as any in China’s history.

The Grand Coronation Palace contains the Imperial Dragon Throne, and is at the heart of the Forbidden City. The pillars and walls are of deep crimson; the eaves and woodwork are painted and decorated with golden dragons. Today, the Double Tenth, the white marble balustrades and terraces were set off by the flags of the Allied nations. The weather was brilliant. Sunshine gleamed off the yellow glazed tiles on the roofs.

The car carrying our small British party approached the Forbidden City through the streets of Beijing through cheering crowds under triumphal arches hung with the flags of the ‘Big Four’ nations: China, Great Britain, the United States and Russia. We drove through packed throngs of excited people with perspiring soldiers clearing a passage for our vehicle. Up to the main fortress gate of the Forbidden City and through the 50 yard tunnel to the square beyond, where we left our car and continued on foot. We walked across and up two flights of steps to the Gate of Supreme Harmony. As we passed through the gate we saw below us the enormous courtyard in front of the Grand Coronation Palace. The square was crowded with more than 100,000 people, filling all the available space - right up to the flights of marble steps and the terraces leading to the Dragon Pavement.

The terraces were decorated with gay bunting, and behind the red pillars of the Palace could be seen the flags of China, Great Britain, the United States and Russia, draping the walls on each side of the entrance hall. The sight was breathtaking, and as we made our way through the lines of soldiers and up the three flights of steps to the Dragon Pavement, a roar of cheering arose and we felt for a moment as if we were the focus of the universe.

At the top of the steps, standing on an Imperial Dragon carpet was a table with the surrender documents.

The Chinese authorities had wisely allowed plenty of time to assemble, and the groups of representatives, each of us wearing an official red silk tab, strolled about and took photographs in the sun. Stately long-gowned officials, Chinese generals in their smart high-collared uniforms, American marine and Air Force officers and the British party – me, the senior official from our embassy, and two junior officers. We were accompanied by civilian spectators of all nations.

A Chinese General escorted me to sign for the British Army. The documents were four concertina-like books bound in yellow silk and made of absorbent paper to take ink brush writing.

All this time, fresh parties of dignitaries were arriving; each heralded by a wave of cheering. The Senior Officer in charge of Ceremonies then marshalled the official spectators. Foreigners were placed on the left and Chinese on the right, with our backs to the Coronation Palace. A military honour guard lined the sides, space being left in front for the Japanese.

When all was ready, the Master of Ceremonies instructed the civilians to remove their hats, and for us military men to salute as the War Zone Commander, General Sun Lien Chung, came out from the Palace into the sunlight followed by his aides.

One of the aides called for the Japanese delegates to be brought forward. A roar indicated the progress of the Japanese military party as they walked the two hundred yards across the huge courtyard surrounded by Chinese spectators. As they climbed the three flights of steps, the roar became a triumphal shout. Seven long years of subjugation ended by the humbling of these officers, about to surrender their swords on the spot where defeated enemies of China have given-up their symbols of power for the last five hundred years.

Forming a line in front of General Sun, the Japanese came to attention, saluted and filed to the left where they stood rigidly. The general commanding the 47 Japanese divisions in China was then called forward to sign the surrender document. He walked to the table and signed with the brush pen provided. General Sun then signed the documents. The next order was “You will now surrender your swords”. With their senior general leading, the Japanese officers filed one by one to the table, unhooked their swords and lay them down. Forming up once more they saluted, turned and marched off to the right. General Sun saluted, turned away and walked back into the Grand Coronation Palace. In its dim pillared depth could be seen the huge Dragon Throne.. The spectators were then invited to drink a toast to the Allies.

Our leaving was another triumphal procession. Once again the crowds clapped and cheered as we made our way through the vast courts and palaces and moved from the fifteenth back into the twentieth century.

I felt drained of emotion. The scene had been too monumental and colourful for reality. The acres of golden tiles, the deep crimson walls, the marble balustrades and the cheering crowds. Such a scene happens only once in an age, and this surrender was for China the supreme moment of the Japanese defeat.

This must have been the most brilliant and stirring surrender in Asia; perhaps in the whole world. But as communications were bad it was hardly reported outside China.

AFTER THE CEREMONY

The following two months were an anti-climax. I was involved in reclaiming the old British Embassy. The American military presence continued to grow. Foreign diplomats returned, and there was much social activity.

On December 12 I closed the Force 136 office and left Beijing to take up a new assignment as Officer in Charge of Signals in Hong Kong. Then in March 1946, I was shipped home to England, and left the Army. Later in the year I entered Cambridge University to read economics, followed by theology, and a new life in the Methodist Church. How wonderful to see an end to the fighting after six years of war, and to return to family and home after such a long separation !

John Stanfield,

Sherborne, Dorset, England

July 2015.